New Insights on Non-Native Herpetofauna in the Carribean

Posted on 3 July 2024

Last week, the iEcoLab published a new paper titled “Non-native herpetofauna of Aruba island

(Caribbean): patterns and insights.” The paper was authored by Gianna Busala, an

undergraduate member of our lab and part of the prestigious Temple Science Scholars Program,

along with Dr. Jocelyn Behm and Dr. Matt Helmus. Busala collected and compiled a database

from the literature on introduction pathways, introduction years, source locations, native

ranges, establishment outcomes, habitat use, and ecological impacts for 15 non-native

herpetofaunal species in Aruba. These data were used to identify introduction patterns on

Aruba and highlight areas of data deficiency, which can inform future research and help slow

the introduction of non-native species. You can read the paper below.

Busala, GM, MR Helmus, JE Behm. in press. Non-native herpetofauna of

Aruba island (Caribbean): patterns and insights. Biol Invasions.

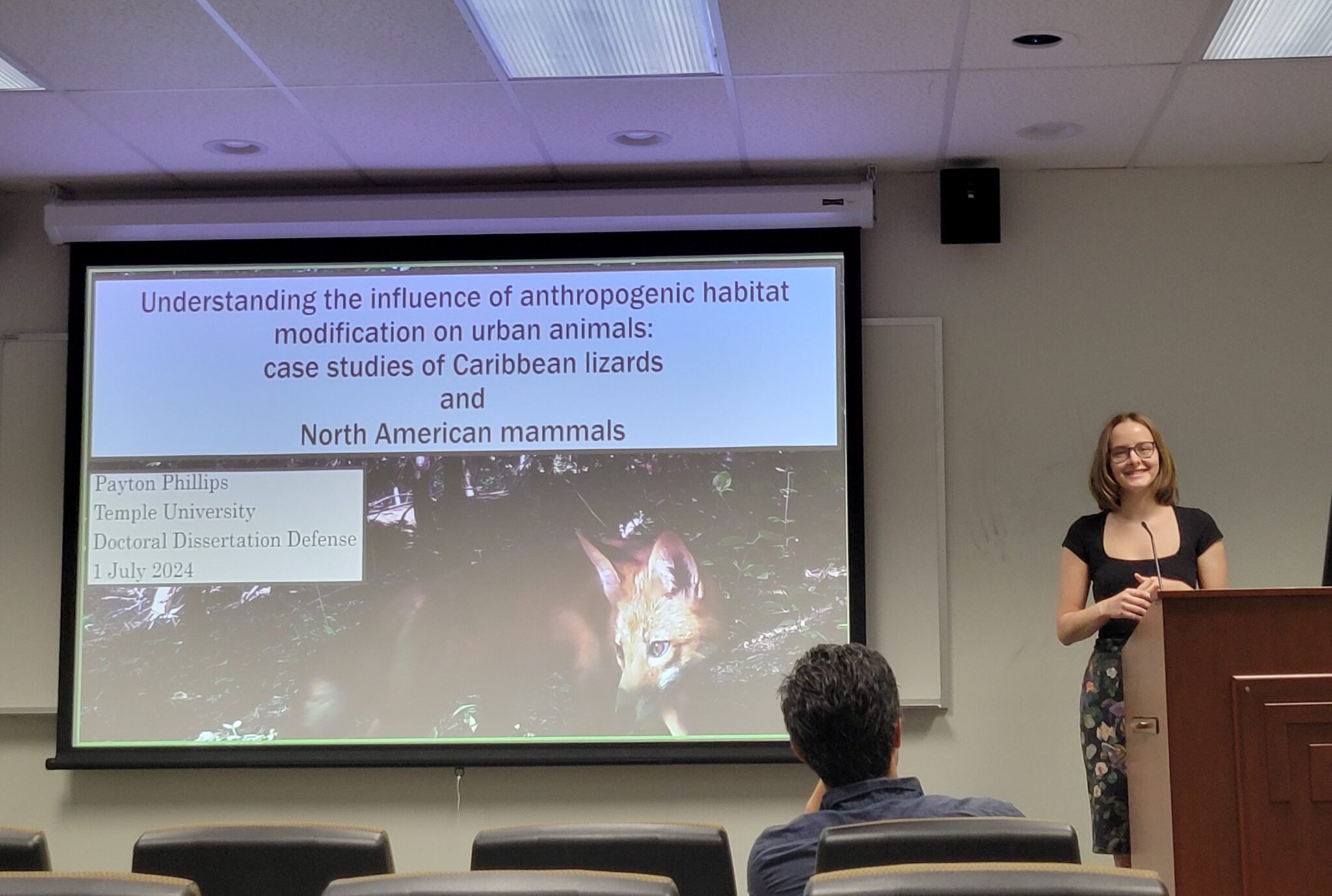

Payton Successfully Defends Her PhD Dissertation

Posted on 2 July 2024

On Monday, Payton Phillips successfully defended her doctoral thesis titled “Understanding

the influence of anthropogenic habitat modification on urban animals: case studies of

Caribbean lizards and North American mammals.” She presented a brilliant overview of her

three thesis chapters in an engaging and accessible manner.

In her presentation, Payton discussed the influence of urbanization and road networks on the

dispersal of three lizard species in the Caribbean, the behavioral responses of

urban-adapted mammal species to urbanization across temporal and spatial scales, and the

effects of landscape-scale urbanization and local-scale vegetation density on tick-borne

disease dynamics.

The results from these chapters enhance our understanding of how human-induced changes

impact urban animals. Some of Payton’s research has already been published, which

you can read here.

Payton has been a valued member of the iEcoLab since 2018, and she will be greatly missed.

She is moving on to a postdoctoral position at the Savannah River Ecology Laboratory at the

University of Georgia, where we are confident she will achieve great things. We wish Dr.

Phillips the best of luck in her future endeavors!

Urban Development Effects Lizard Dispersal

Posted on 24 June 2024

Payton Phillips and iEcoLab members and collaborators made the cover of Diversity and

Distributions with their article titled “Dispersal restriction and facilitation in species

with differing tolerance to development: A landscape genetics study of native and introduced

lizards.”

Phillips et al. discovered that the influence of urbanization on lizard species

varies. The native gecko, Phyllodactylus martini, is highly sensitive to development and

faces significant barriers due to roads while the introduced gecko, Hemidactylus mabouia, is

remarkably resilient and even benefits from human-facilitated movement. The native Anolis

lineatus presented a more neutral response to development occasionally benefiting from human

facilitated long-distance dispersal. These findings help understand how we can better manage

and protect wildlife in our rapidly urbanizing world.

Cover photo credits to Dr. Matthew Helmus

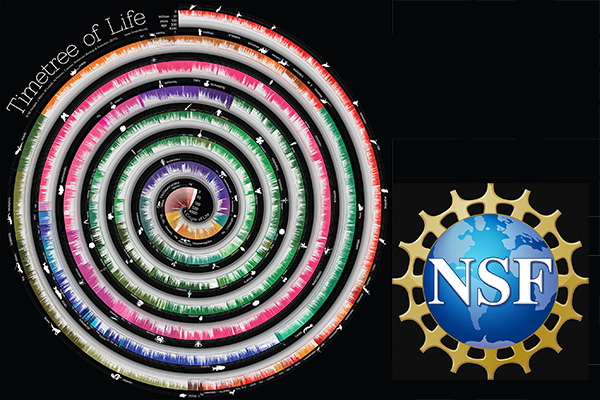

Lab Awarded NSF Grant for Building the Timetree of Life

Posted on 14 February 2024

NSF has awarded $1 million to build a comprehensive timetree of life representing the evolutionary history of biodiversity and deliver it via TimeTree [LINK]. Led by Blair Hedges and Sudhir Kumar, it is a collaborative effort with Zoran Obradovic and Caryn Babaian. The general public and experts can query the website to obtain the divergence time of any two species, a timeline, and a timetree of any group of species. The timescale of life, delineating when species diverged from common ancestors, serves as a framework for understanding biology and is fundamental context for other fields of science such as geology, chemistry, and biomedicine. The advancements in genomics and computing have refined this timescale, resulting in the publication of thousands of evolutionary trees scaled to time, known as timetrees. Users can obtain the divergence time of any two species, a timeline showing all evolutionary splits back in time, and exportable timetrees of any group or from a custom list of species. Events in geological and astronomical history, such as asteroid impacts, oxygen levels, and solar luminosity, are integrated into the same timescale with species timetrees and timelines, facilitating interdisciplinary research and applications in areas like molecular biology, conservation, and medicine. The new TimeTree resource will implement new algorithms, tools, and application programming interfaces to speed, improve, and increase the efficiency of timetree curation and data mining. It will have a new online educational component designed for K-12 and college students. Image: A spiral timetree of 50,632 species.

Back to Top

Editor – S. Blair Hedges